Written by: Edward Y., Adult Services Manager

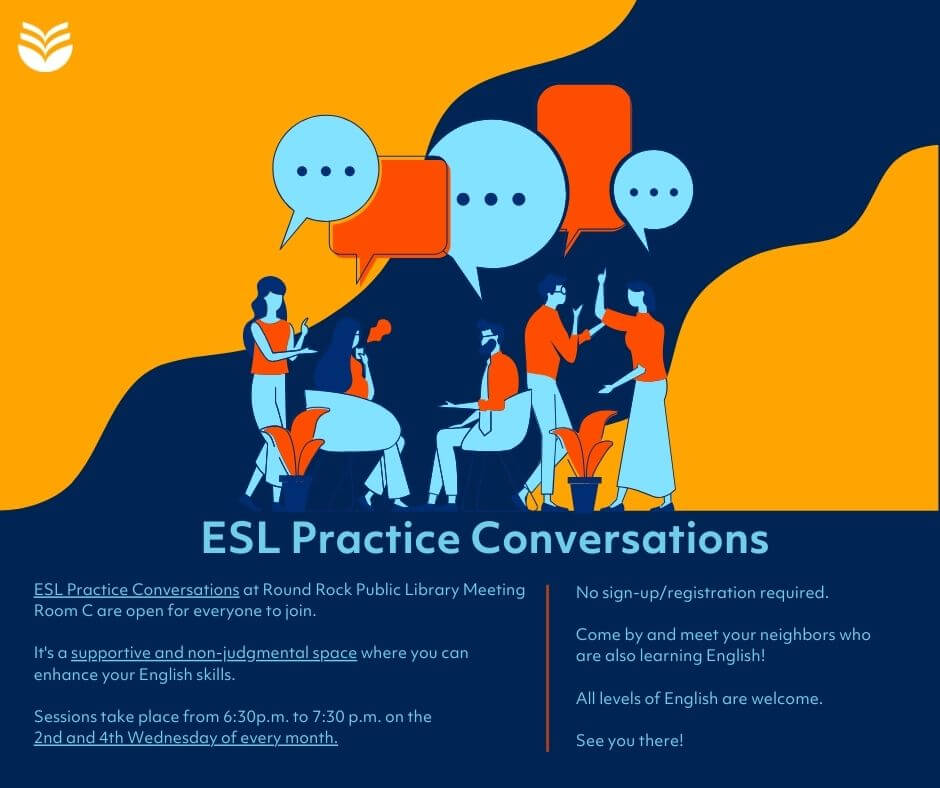

In March of 2024, I started leading a small program for an hour on Wednesday evenings. Occurring twice a month, on the second and fourth Wednesdays at 6:30 pm, RRPL hosts a gathering of folks trying to learn English. Called, “ESL Practice Conversations”, attendees are offered a welcoming and non-judgmental setting to practice English alongside others experiencing the same challenge. Tonight, April 10th, will be the 3rd session.

So far, we’ve started humbly, with three ‘students’ attending each time. In our first session, one attendee was from Colombia, the other two from Mexico. In the next session entirely new folks showed up, two from the Ukraine and one from Russia. Despite this significant geographic diversity, both groups coincidently exhibited the same pattern, one older attendee who was a true beginner to English and struggling, and two younger people with more confidence in English. It was incredibly heartening to see how willingly in both cases the two younger patrons, (who also coincidentally in both cases arrived together and were obvious friends or family), helped the older learners, despite their being strangers.

I started this program in response to requests from many students who attend our more formal ESL classes. We received both written and oral suggestions that the library offer an organized conversation program, allowing those students to freely try out their burgeoning language skills without having to worry about a native English speaker’s potential annoyance or impatience. Despite not being a professional educator, I believed I would be good at this since I love learning about other cultures, have a lot of confidence in my geography knowledge, and am a patient fellow that enjoys helping people learn and express themselves.

Regardless of whether I’m justified in that confidence, (only steady attendance of future sessions will reveal if I’m right or wrong about being an effective leader of these conversations), the classic trope of ‘the teacher learns from her students’ has certainly been applicable to our first two ESL conversations. My preparation ahead of the first class turned out to be far too detailed; I had so much I wanted to say and express about the intentions of these group conversations that I occupied far too much ‘talking time’, foiling the entire point of the program – getting the learners to practice their own English. In effect, I gave too many opportunities for them to just agree with what I was saying and not enough practical instigation to push them to talk more than me.

Also, I didn’t choose topics with enough general appeal. I thought I had prepared correctly for this consideration, planning on having them talk about places for recreation that they enjoy, either here in the U.S. or in the nations they emigrated from. However, this presumed they’ve had the time or energy for much fun, which was especially problematic because the majority of them immigrated to the U.S. to escape extreme difficulties, and because they had very limited employment options, many of them had to work extremely long hours at multiple jobs.

My other principal mistake as the coordinator of these talks was suggesting what they meant to say too often. I quickly realized that if I offered a way for them to say something, either to improve grammar or to lean a bit more colloquial in their phrase choices, they simply would agree, and it was then very difficult to push them to either repeat or try their own version again, because that’s a bit too elementary school feeling for accomplished adults to enjoy as a fun conversation.

So, surprisingly, what worked much better, (usually by the second half of each hour, when it started becoming clear that I wasn’t pushing them to try more English responses), were the moments of improvisation, when I would riff off of something they said, and follow up with related questions. Duh, like a conversation! So, I’ll start with some commonplaces like, “What did you have for lunch today?”, or “How did work/school go today?” and then keep it more natural.

And a final point about the teacher learning from the students: I’ve learned so much I didn’t have any clue about from these brave immigrants, (so much for the cultural-awareness of Mr. “I have a Masters In History So I Know A Lot About The World”)! I’ve learned that people in Russia and the Ukraine love Georgian food, perhaps in a similar way the people in the U.S. are obsessive about Mexican food, and that there are Georgian restaurant chains catering to this preference throughout those much colder regions. Also, I learned that the power of love between even multi-decade marriages can be extreme, as one Ukranian attendee, from the war-torn, battlefront city of Kharkiv, has decided to return despite the extreme peril because she misses her husband too much. He’s a man in his late fifties fighting in the army; my late forties back has sympathy spasms just imagining what his middle-aged body must be enduring.

Which begs the question, how can we have so much antipathy as a nation towards so many of our immigrant neighbors? The risks and struggles they endure to get here, and the incredible difficulty of learning English and an entirely new set of national laws and requirements, makes them the ideal neighbors. These are people that strive in life, that make things happen in a dynamic way that non-immigrants like me can only imagine. Who better to join our American Experiment?